Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium L.) has been used as a culinary and medicinal herb since antiquity. One of its popular English synonyms 'Pudding Grass' clearly indicates that this mint-like herb was a popular ingredient in certain kinds of puddings. It is still used in some regional versions of black pudding, such as those made in Bury in Lancashire. However, the popularity of pennyroyal as a kitchen herb waned during the course of the nineteenth century and nowadays it is rarely used in a domestic context. This is almost certainly due to two rather worrying factors. The first of these was the traditional folk belief that the plant could be used to induce abortions and should therefore be avoided at all costs by pregnant women. The second was the more recent discovery that the essential oil of pennyroyal is highly toxic and its consumption has frequently proved fatal to both humans and animals - and probably to insects too, as over the centuries the plant was widely used to discourage fleas, lice and other six legged pests. It should not come as a surprise then that nowadays it is not to be found on the supermarket herb and spice shelf. However, the dried herb can be obtained from herb suppliers and some still make a tisane from it, the consumption of which in moderate quantities is considered to be pretty harmless, as is its inclusion in small quantities in black puddings.

Pennyroyal was also once employed as a flavouring for other members of the pudding family, including an unusual herb dumpling, a recipe for which was included in Charlotte Mason's The Lady's Assistant (London: 1773).

|

| Like many other puddings, Mrs Mason's pennyroyal dumplings were boiled in cloths. |

Mrs Mason's pennyroyal dumpling is closely related to another commonly made pudding called 'green pudding'. Some think that this was consumed as a spring tonic, rather like the herb pancake known as a tansy. Green puddings were certainly designed to be eaten during Lent and at Easter. Pennyroyal is frequently an ingredient, though it is often just one of a medley of different garden and wild herbs. The late seventeenth century recipe below also includes spinage, savory and thyme.

|

This recipe for green puddings is from the unpublished Receipt Book of Elizabeth Rainbow (d. 1702). It instructs us to 'boil' (fry) the little puddings in butter in a dish, rather than boiling them in a cloth. Elizabeth was the wife of Edward Rainbow (1608-84 ), the bishop of Carlisle. Photo © Dalemain Estates.

|

Although Elizabeth Rainbow's recipe called for the green puddings to be fried, they were more usually boiled in a cloth, like Mason's pennyroyal dumplings. However, the recipe below from the manuscript receipt book of Elizabeth Birkett (aka Brown) dated 1699, specifically instructs us to boil her pudding in a bag, rather than a cloth. Her recipe does not include pennyroyal and is flavoured with strawberry leaves, violet leaves, thyme and marjoram. Like Mason's and Rainbow's dishes, the basis of the pudding is grated bread.

|

| A green pudding recipe from the manuscript receipt book of Elizabeth Birkett (1699) of Townend Farm, Troutbeck, Cumbria. Photo courtesy of Kendal Public Record Office. |

|

| Elizabeth Birkett's' Greene Pudding' 1699. This pudding was wrapped in a caul before being boiled in a bag |

Both Elizabeth Rainbow and Elizabeth Birkett wrote their recipe collections in the late seventeenth century in the English Lake District, a part of the world where green or herb puddings are still made today, most usually at Easter. To some Cumbrian locals these latter day paschal puddings are known as 'Easter Ledge Pudding', 'Easter Ledges' or 'Easter May Giants'. These curious terms are also local vernacular names for bistort (Persicaria bistorta (L.) Samp.), one of the main ingredients of the dish. Incidentally another regional name for bistort is 'pudding grass'. Other herbs included in the mix are alpine lady's mantle, nettle leaves, giant bellflowers and black currant leaves. However, I have not yet come across a modern Lakeland recipe which calls for pennyroyal. Both Rainbow, a bishop's wife and Birkett, the wife of a yeoman farmer, used wheaten bread as a basis for their herb puddings. But in their day only the well-off could afford white bread, because wheat was very difficult to cultivate in the wet, cool climate of the Lake District. Oats and barley were the staple cereals for the poorer farmers. The surviving modern Cumbrian recipes for herb pudding are made with a base of either oatmeal or pearl barley, so it is likely that they have evolved from a more low status version of the dish, rather than the somewhat genteel puddings described by the two Elizabeths. This may well also explain why modern versions of Easter Ledges Pudding are made from foraged wild plants, which are free, rather than the Mediterranean herbs that were grown in the gentlewoman's herb garden. As green puddings became unfashionable among the increasingly more sophisticated gentry of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the conservative Lake District peasantry continued to make their version of the dish, which has survived to this day among the farming community. Though of course there seem to be no surviving printed recipes for their dish earlier than the twentieth century.

|

| Easter Ledges or Easter May Giants, two of a number of Cumberland/Westmorland dialect names for bistort (Persicaria bistorta (L.) Samp.). The leaves of this plant, which like pennyroyal is sometimes called 'pudding grass', are picked when young and tender. |

A friend and neighbour of mine, who gathers her Easter Ledges from the same stream-side in our village as I do, recently showed me two precious family heirlooms - the pudding bags used by her mother and grandmother in which they boiled the Easter herb pudding mix. These venerable 'clouts' are made from 'ticking', a strong weave of textile used for making mattresses and pillows. They are stained with the juice of generations of herbs. Both bear a few campaign scars which have been neatly repaired. I suspect that the 'bag' mentioned in Elizabeth Birkett's greene pudding recipe must have looked just like these hoary veterans.

|

| Two well-used veteran Westmorland herb pudding bags. Photo courtesy of Jean Scott-Smith |

So herb puddings could be fried in butter, or boiled in a cloth or bag. In Elizabeth Birkett's recipe for green pudding she tells us 'to wrap it in a mutton caul' before you boil it in a bag. The caul fat of calves and lambs was much used in the early modern period for holding fragile ingredients together in dishes of this kind. The caul or omentum, is the inner lining of the animal's abdomen and its anastomising network of veins of fat on a thin transparent membrane give it the appearance of very delicate lace. Not only does it work very well as a wrapping, but the fat also bastes the outside of the pudding. In some regions of England caul is still used for making a fatty jacket for wrapping the little pork offal 'puddings' known as faggots or savoury ducks.

'Caule of veale, or lamb' turns up in another of Elizabeth Rainbow's recipes, this time in a pie filled with little round puddings flavoured with herbs, including pennyroyal. The recipe is acknowledged as one contributed to Elizabeth by a Lady Sedley. This was Catherine Sedley, daughter of John Savage, Earl of Rivers, who married Sir Charles Sedley the poet and courtier in 1657. A surviving book of receipts (mainly medical) dated 1686 by Lady Sedley survives in the library of the Royal College of Physicians. Lady Sedley's husband, a favourite companion of Charles II was noted for his drunken, often lewd behaviour.

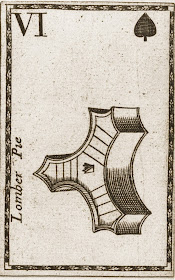

A lumbard pye, sometimes known as a lumber pie, was a pie filled with meat balls, or as in this rare example, miniature green puddings. In fact, the small caul wrapped puddings in Lady Sedley's Lumbard Pye are very similar to Charlotte Mason's pennyroyal dumplings cited earlier in this post. Both have pennyroyal as a principal flavouring and both contain currants. However, Lady Sedley's little pennyroyal dumplings are wrapped in caul and baked in a pie with butter, marrow and dates. The pie is later filled with a 'caudle' made of wine, egg yolks and sugar. Unlike most of the lumber pie recipes from this period, the filling contains no meat. Lady Sedley's little pie-baked puddings are not a hundred miles away from the modern butcher's faggot in construction, if not in ingredients. Lumber pies however, were luxury dishes found only at the tables of the rich.

Elizabeth Rainbow also gives a recipe for a more conventional Lumbard Pye, this time filled with 'round balles' made of minced lamb or 'the brawn of a cold Capon' (cooked chicken's breast). Unusually each ball contains a 'soft centre' in the form of an egg yolk and a 'good piece of marrow'. Each one is wrapped in an endive and/or? sorrel leaf before they are baked with a rich assortment of artichoke hearts, skirrets, potatoes, chestnuts, dates, hard egg yolks, marrow, barberries, grapes, preserved orange peel, apricots or other preserved fruit. Like Lady Sedley's, the pie is filled after baking with a caudle and put back in the oven to warm through. I will be making both of these lumbard pies over the next few weeks and will eventually post an article about the full process.

The author of the above recipe was Elizabeth Nodes (b.1648), who married Charles Fane, the 3rd Earl of Westmorland in 1665. She probably met Elizabeth Rainbow in London, most likely at Suffolk House, the London home of the Earls of Suffolk. Little is known about Lady Westmorland, but a fine portrait of her was painted by John Michael Wright.

|

| Elizabeth, wife of Charles Fane, 3rd Earl of Westmorland, by John Michael Wright |

Most of the printed cookery books and many manuscripts of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century give at least one recipe for lumber, lumbard or lombard pies. They seem to have been very popular. The name is usually assumed to be a corruption of Lombard, suggesting some Italian link, but its true origin remains obscure. The herald Randal Holme in

An Anatomy of Armoury (Chester:1688) defines it thus,

'Lumber pie, made of Flesh or Fish minced and made in Balls‥with Eggs‥and so Baked in a Pye with Butter'.

Over the course of the past three decades I have made many different lumber pies. It is my favourite English pie of the early modern period. On my Pie and Pastry course I frequently teach my students to make one of Robert May's versions of the dish, usually from the recipe below, though over the years we have also made two of his fish based lumber pies - one of sturgeon and the other with salmon.

To Make a Lumber Pye

Take some grated bread, and beef-suet cut into bits like great dice, and some cloves and mace, then some veal or capon minced small with beef suet, sweet herbs, fair sugar, the yolks of six eggs boil’d hard and cut in quarters, put them to the other ingredients, with some barberries, some yolks of raw eggs, and a little cream, work up all together and put it in the caul of veal like little sausages; then bake them in a dish, and being half baked have a pie made and dried in the oven ; put these puddings into it with some butter, verjuyce sugar, some dates on them, large mace, grapes, or barberries, and marrow - being baked, serve it with a cut cover on it, and scrape sugar on it.

From Robert May,

The Accomplisht Cook (London: 1660).

|

A lumber pie made on a recent pie and pastry course from Robert May's recipe above. Each meat ball has been wrapped in caul. The bright red berries are barberries.

|

|

| May tells us to finish the pie with a cut lid scraped with sugar |

Designs for the pastry cases for lumber pies abound in seventeenth and early eighteenth century cookery books. Many were quite elaborate and often had very eccentric shapes, as those reproduced below.

|

| Lumber pie designs from Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (London: 1660) |

|

| I have posted this scan from my paper 'Illustrations in British Cookery Books', 1621-1820 in Eileen White (ed.), The English Cookery Book - Historical Essays. (Prospect Books, Totnes:2004) to illustrate a point I make in my reply to Kaprifolia's comment below. |

ff. 18v-19. Courtesy of British Library

ff. 18v-19. Courtesy of British Library