Or The Pastry Kunstkammer

|

The Burghley Nef. Nautilus shell with parcel-gilt silver mounts, raised, chased, engraved and cast, and pearls. France 1527-1528 Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum

|

Christmas is a time for celebrations and parties, though the style of our entertainments has changed over the centuries. In the past, the really big day for a blowout was the last day of the Christmas holiday - Twelfth Day. Almost half a century ago I came across the passage below in Robert May's The Accomplisht Cook (London: 1660) for a twelfth day entertainment. I was in my early teens when I first read this hilarious account of a slapstick performance at the end of a great Jacobean feast and it really fired my schoolboy imagination. Since then the passage has been much quoted and with its pies full of skipping frogs and flying birds, is the sort of thing that reinforces the modern reader's conception of early modern period dining as a 'Baldrick-style' free for all. If you have never come across it before, please read it now. It is great fun.

|

| From Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (London: 1660) |

Just the sort of thing that television producers of 'food history' programmes and tabloid journalists love. Though in in my view this kind of thing can act as a serious distraction, because it tends to reinforce the 'four and twenty blackbirds' stereotypical perception of British food history, when the truth about our gastronomic past is much more complex.

However, when I was in my mid-twenties back in the 1970s, I actually had a bash at re-staging the whole thing, not to celebrate twelfth day, but for a friend's twenty-first birthday party. With three pet canaries (unharmed) and five frogs from my father's pond (slightly puzzled by the experience but who lived to tell the tale) I made some hollow pies according to May's instructions as temporary homes for these creatures. I proceeded to construct a paste-board (cardboard) armature in the form of a ship's hull and covered it with pastry. I furnished it with cannons made out of kickses (hollow cow parsley stems) and foolishly charged them with some homemade gunpowder. The rigging I made from twine and the sails from wafer paper. I also constructed a castle out of pastry and armed it with the same kind of ordinance. The pastry stag proved more difficult, but I owned a copy of Conrad Hagger's marvellous Neues Saltzburgisches Koch-Buch published in Augsburg in 1719 and made a seated pastry stag along the lines he illustrates. I concealed a pig's bladder inside the stag, which was half filled with red wine and tied with cord so it did not leak.

|

| Diagrams for making pastry deer from Conrad Hagger, Neues Saltzburgisches Koch-Buch (Augsburg: 1719) |

We blew the insides out of a dozen eggs, melted candle wax over one of the holes, filled them with rosewater with a syringe and sat them upright in the salt sea around the pastry galleon and stag. All the pies, the stag, ship and castle were all gilded 'over in spots' as in May's instructions. Unfortunately, I overloaded the cannons on the pastry castle with too much gunpowder and when we lit the fuses, the shattered pastry battlements blew across the table, knocking one of the stag's antler's off. The cannons on the ship behaved a little better, though one of the sails went up in flames. Until then I did not realise how well rice paper burns when ignited. Fortunately a quick thinking guest, in the spirit of the occasion put the flames out by emptying a couple of rosewater filled eggs over the ship's rigging.

As to the frogs, when the lid of their pie was lifted, they refused to budge and despite the noise of the cannons just sat there looking comatose. May explains what should have occurred, 'Out skip some Frogs, which make the Ladys to skip and shriek', but this did not happen. The frogs having found a nice dark warm home, they decided to hibernate. The ladies present hardly noticed them. My friend Andrew's tame canaries did fly out of the pie and took off around the room, but failed to put the candles out. Andrew eventually coaxed them back into their cage. I do not think the 'blood stains' created by the red wine when it poured out of the stag were ever successfully removed from that rather expensive linen table cloth belonging to Andrew's mum. Forty years later I still feel guilty about it. Seen from today's point of view, the whole thing was ill-conceived and a health and safety nightmare. We were lucky that the house did not catch fire.

|

| Examine this carefully and you will see that the pies and birds are gilded 'over in spots', just as Robert May describes in Triumphs and Trophies of Cookery. Jan Breughel the Elder, An Allegory of Taste (detail). 1618. The Prado, Madrid |

Though terribly misguided, I must admit that my juvenile recreation of this event was a lot of fun. But the question I asked myself afterwards was did this sort of thing really happen at great feasts, or was it just something that May invented? He tells us that before the English civil war, 'These were formerly the delights of the Nobility, before good Housekeeping had left England'. But are there any accounts of events like this being held at court or in some of the great ducal palaces?

|

The nef was an important symbol of status on the medieval table. From the Grimaldi Breviary. Ghent and Bruges 1515-20. Ms. Lat. I, 99. Courtesy of Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice.

|

There are some elements of truth in May's account, though we have to look to the European mainland to find the evidence. Take May's pastry ship with its firing cannons for instance. In France and the German speaking parts of Europe, there had been a custom dating back to the medieval period of embellishing the aristocratic table with a miniature ship called a nef, usually made of goldsmith's work. These frequently served as ceremonial salts and graced many a high status renaissance table. Good examples of these precious objects have survived, such as the Burghley Nef (1527-28) in the Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrated at the beginning of this post. In the second half of the sixteenth century, in German towns such as Augsburg and Ulm, clockmakers started turning their hands to making nefs which doubled up as table automata. Some even had crew members who climbed up the rigging or played musical instruments. Others were fitted with miniature cannons which could actually be loaded with gunpowder and fired, like the example below by Ulm silversmith Joss Mayer.

|

| Table centrepiece or nef in the form of a galley by Joss Mayer (active 1573-1609) Ulm. Silver gilt. The guns can be loaded with powder and fired. Courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. |

|

| Table centrepiece in the form of a ship. Hans Schlottheim (1544-1624). Silver gilt, brass, enamel with oil painted sails. A mechanism driven by a mainspring and fusee is concealed within the hull. Augsburg 1585. Courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna |

Another remarkable survival of a nef style table automaton is also to be found in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It was made for Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) by Augsburg silversmith and clockmaker Hans Schlottheim (1544-1624). A small statuette of the emperor stands on the deck. The ship's masts fly flags emblazoned with the imperial double eagle, so the vessel represents the Hapsburg Empire itself securely captained by Rudolf. The ship actually moves across the table as if putting to sea while miniature musicians play sackbuts and timpani, the finale being a salvo fired by the cannons. A marvellous video of the whole performance has been produced by the curatorial staff of the Kunstkammer in Vienna which I have included below. Please, please play it, as it is an absolute treat. And if you get a chance, visit the superb new Kunstkammer layout in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum, where you will be able to see the real thing and a number of other remarkable table automata.

Although made from precious metals with oil painted sails, Rudolf II's warship is highly reminiscent of May's more humble pastry version. May was born in 1588, just three years after Schlottheim made his ingenious galleon for the Hapsburg emperor. As a child apprentice cook he trained in Paris between 1598 and 1603 and it is possible that he may have come across similar table automata while in France. Fame of the remarkable example in Emperor Rudolf's kunstkammer had certainly spread across Europe by this time.

Conrad Hagger's designs for pastry stags were published much later - in Augsburg in 1719. Like May, Hagger was an 'old school' cook who worked for the prince archbishop of Saltzburg, a conservative ecclesiastical patron who presided over a table that was more in the style of a renaissance prince than of an enlightenment cleric. Remember, Augsburg, where Hagger's book was published, was also the town where Schlottheim fabricated his Schiffsautomat for the emperor's table.

So, we have parallels for May's cannon firing ship and his pastry stag, but what about the pastry castle and the pies filled with birds and frogs? Pies in the form of castles go back a long way. In the medieval recipe collection The Forme of Cury (1390s), there is a receipt for a complex pastry in the form of a battlemented fortress called a Chaselet (little castle). Each tower is stuffed with a different filling and presented to table ardent, that is flaming with burning brandy. William Rabisha in The Whole Body of Cookery Dissected (London: 1661) gives some very similar recipes, including this 'orangado pie' in the form of a castle,

|

| An orangado pie in the form of a castle from William Rabisha, The Whole Body of Cookery Dissected (London: 1661) |

These curious structures were also made out of sugar paste. The extraordinary mould below, which is in my own collection, was designed for making a battlemented gatehouse out of gum paste.

So what about the blind-baked pies filled with live birds? Well that is a very old joke, the earliest recipe in English being published in 1598 in a translation of Giovanne de Rosselli's Epulario,

|

| From Epulario, Or, The Italian Banquet, (London: 1598). |

|

Title page of Giovanne de Rosselli, Epulario quale tratta del modo de cucinare ogni carne, ucelli, pesci, de ogni sorte, e fare sapori, torte, e pastelli al modo de tutte le Provincie. (Venezia: 1555). Rosselli's work was first published in Venice in 1516. It heavily leant on the Libro de arte coquinaria by Maestro Martino, though its content varied in later editions with extra recipes being added by the publishers.

|

Here is Rosselli's original recipe, from which the English version above was translated. Per fare pastelli volativi literally means 'To make pies of flying birds'.

|

| The original recipe in Italian for the pie filled with living birds from Giovanne de Rosselli, Epulario. (Vinegia: 1594). |

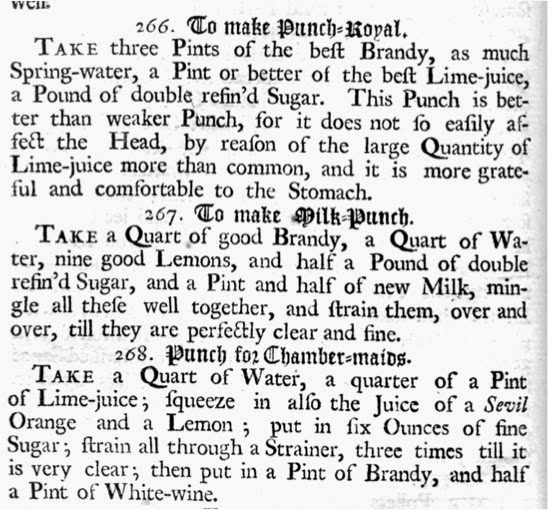

So to sum up, May's extraordinary

Triumphs and Trophies of Cookery passage contains elements of culinary extravaganzas from all over Europe. The eccentric live bird pies appear to have been based on the

pastelli volativi of Renaissance Italy. The

nef, which originally emerged in France was fiddled around a bit by the automaton makers of Augsburg, who added a few firing cannons and musical sailors for dramatic effect. The pastry stag featured at Imperial Hapsburg bean-feasts. Even May's use in the title of the passage of the word 'triumph' is a rare reference in English to the Italian name for an elaborate table ornament made of sugar -

il trionfo.

This kind of thing had died out in England well before the Civil War, though if Hagger's illustrations are based on actuality, similar entertainments were still being carried out in the Archbishop's palace in the Hapsburg city of Salzburg as late as the early eighteenth century. Four years after Hagger's book was published in Augsburg, John Nott in

The Cook's and Confectioner's Dictionary (London: 1723) re-wrote May's text, presenting it as an antiquarian curiosity. Here is his version. He refers to the long dead May as an 'ancient artist in cookery'.

'Divertisiments' and 'diverting Hurley-Burleys' of this eccentric nature did take place at some European courts, though it is likely that many of the real triumphs of the table were made by the goldsmiths and clockmakers of renaissance Augsburg rather than pastry cooks. Below is another video of a remarkable table automaton made for the imperial Hapsburg kunstkammer, this time by the Augsburg goldsmith and inventor Achilles Langenbucher (1579-1650). He fabricated this wonderful triumphal car with Minerva in Augsburg in 1620. Like Schlottheim's Schiffsautomat, this Triumphwagen travels down the middle of the table, its two horses rearing up as it goes. Do watch it. Again, it is a remarkable insight into the lavish entertainment style of the renaissance Hapsburg emperors.