|

| The King's Christmas Pudding made from the 1927 recipe published by the Empire Marketing Board |

Towards the end of our previous post

The Pudding King we touched on the subject of plum pudding as a potent emblem of British patriotism. We also explained how the dish was reinvented in the early decades of the twentieth century for a variety of political reasons, including the emergence of its role as an imperial symbol. The story about plum pudding which follows is from a time when Britains's vast empire included almost one fifth of the world's land surface and one quarter of its population. Its colonies provided the mother country with a remarkable range of raw materials, including many food items. It is ironic that a number of celebratory British food stuffs are made from ingredients that cannot be grown in the British Isles - plum cake, plum pudding, mince pies and marmalade all depend on exotics imported from warmer climates.

It is often said that plum pudding was first consumed at Christmas in the medieval period and then banned during the Commonwealth by Cromwell until revived by George I in the early eighteenth century. However, we have not found any contemporary sources which verify these claims. So far, the earliest reference we know that firmly associates plum pudding with Christmas is in the diary of Henry Teonge, a British naval chaplain who served on board a number of Charles II's ships. On Christmas Day 1675, somewhere off the west coast of Crete on board His Majesty's Ship Assistance, he wrote in his journal,

'Our Captaine had all his officers and gentlemen to dinner with him, where wee had excellent good fayre: a ribb of beife, plumb-puddings, minct pyes, &c. and plenty of good wines of severall sorts; dranke healths to the King, our wives and friends; and ended the day with much civill myrth.'*

Perhaps HMS Assistant's cook bought the dried fruit, sugar and spices to make the pudding in the market at the ship's last port of call, the Levantine town of Iskendarun.

From at least the time of Henry Teonge until the Great War, roast beef and plum pudding were the British celebratory foods of choice for all sorts of festive occasions, not just Christmas. By the first half of the nineteenth century, cookery authors such as Elizabeth Hammond and Eliza Acton had started to call it Christmas Pudding rather than Plum Pudding, a process that Food History Jottings research assistant Plumcake has discovered had started back in the eighteenth century, or possibly earlier. We will say more about Plumcake's findings in another post.** Charles Dickens also played some part in fixing the pudding as a dish more specifically linked to Christmas. Despite this more specialised role during the Victorian period it continued to be served at occasions such as jubilee ox roasts and other junketings. During the First World War plum pudding took on a new patriotic role as a symbol of solidarity. Embroidered silk Christmas cards showing a pudding struck with allied flags became a popular souvenir, which soldiers sent from the trenches to their loved ones back home.

No doubt these striking images of plum puddings spiked with the flags of the nations had some influence on the members of the British Women's Patriotic League, who in the decade after the Great War urged families to buy Empire goods. In 1922 they inaugurated the first Empire Shopping Week, during which they set up displays of food and produce from Empire countries and encouraged the big West End stores to follow suit. This was a period of unbridled free trade when Californian dried fruit was coming into Britain on the back of an aggressive advertising campaign. The American importers were aware that dried fruit sales in Britain were rather poor other than at Christmas time and attempted to boost the market by publishing advertising leaflets with raisin recipes for cakes and raisin loaves which could be eaten all year round. Australian vine fruit growers were horrified with the American competition, as were the rank and file of the British Women's Patriotic League, who recognised the debt that Britain owed to the Australians for their sacrifices during the war (though of course the Brits also owed a great deal to American troops!). In 1924 they urged the housewife to 'make your Christmas Pudding an Empire Pudding' and to boycott imports from non-Empire sources. They published a leaflet with a recipe which listed ingredients from various Empire countries. The concept of the Empire Christmas Pudding was born.

|

Spiked with both the Australian flag and the Union Jack this giant Christmas Pudding paraded in London in 1925 was sandwiched between a stuffed emu and a kangaroo.

|

In 1925 when the Lord Mayor's Show explored the theme 'Imperial Trade', the Australian fruit growers paraded a huge Christmas Pudding pulled by a team of white horses. Emblazoned on the back of the pudding were the words 'make your pudding of Empire products'. None of these initiatives came directly from the British government, who in these difficult economic times wavered between unfulfilled whispers of protectionism and unregulated free trade. They could not formulate a firm policy on supporting Empire trade and at first were very quiet on the whole issue. However in 1926 they inaugurated a rather ineffective quango called the Empire Marketing Board (EMB), whose main purpose was to research the production, trade and use of goods throughout the British Empire and to promote the idea of 'Buying Empire'.

Taking their initiative from the British Women's Patriotic League, the EMB adopted the idea of the Empire Pudding. A short time before Christmas 1926 they issued a recipe in the form of a poster with an image of Britannia holding a flaming plum pudding surmounted by a union jack flag.

|

| The Empire Marketing Board's first campaign poster. Only a few Empire countries are listed. Courtesy of Public Record Office |

The EMB's campaign was a little late in the day, but they did boost their publicity by asking the ruling monarch King George V if he and the Royal Family would eat the empire pudding on Christmas Day. He agreed and as a result the pudding also became known as the King's Christmas Pudding.

|

| The last ingredient in the 1926 recipe above was a silver 3d. bit 'for luck!' |

Another body which promoted the pudding was the Empire Day Movement, led by the charismatic Irish peer Reginald Brabazon 12th Earl of Meath. Lord Meath masterminded a publicity stunt in which the pudding was made at Vernon House, the headquarters of the Overseas League in London. He ensured this event was filmed for a newsreel called Think and Eat Imperially, which was shown in cinemas all over the Empire, giving the campaign a tremendous amount of publicity. As early as 1909 Meath had realised the power of the cinema as a promotional tool. In that year he commissioned a film of a vast Empire Day gathering in the town of Preston. This remarkable archive movie has survived and I have supplied a link to it at the very end of this posting.

|

| The chef adds Australian sultanas to the mix, while Lord Meath (on the right) looks on |

Meath's vision of Empire saw Britain and its distant colonies as one large extended family. So at his publicity event, he invited representatives of the various empire countries to stir up the pudding. The various ingredients were also delivered to the chef by ushers from each producing nation. The 'pudding spice' from India was brought to the table by two Indian ushers in turbans.

|

| The family tradition of stirring the pudding was adopted by Meath as an emblem of imperial unity |

|

| Meath stirs the 1926 Empire Pudding in the garden of Vernon House |

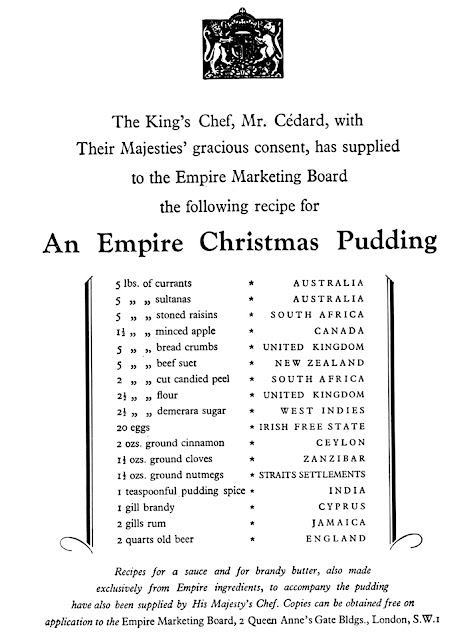

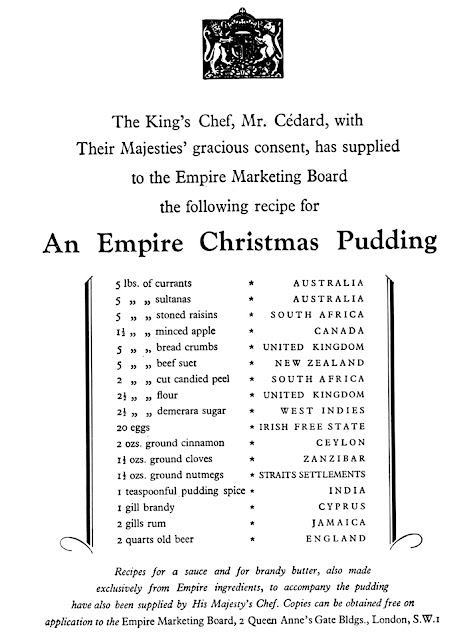

The following year, the campaign took on an added dimension when George V's chef Monsieur Cédard provided a better recipe with a few more nations listed in the ingredients table. The campaign lasted well into the thirties, only fizzling out with the outbreak of World War II. In 1930 a propaganda film called One Family was released to promote the pudding and Empire Trade. In its day it was a complete flop. It was originally filmed as a silent movie in 1929, but to keep up with dramatic new developments in the cinema, a sound track was added to it. The film stars a London schoolboy who notices an Empire Christmas Pudding recipe in his father's newspaper. He lingers on his way to school to admire a display on the pudding in a grocery store and is late for his lessons. During one on the subject of empire geography, he falls asleep and dreams he goes to Buckingham Palace. He meets the king and is sent on a quest to collect the ingredients in the producing countries. It is sixty nine minutes long, but as a period piece is really worth watching. Much of it was actually filmed in Buckingham Palace and there is a tantalising glimpse of the palace kitchen in one scene. I have put a link to the full One Family film at the end of this posting.

|

| Though suitable for a royal palace where puddings were made in vast numbers for distribution to staff as Christmas presents, the large quantites in this recipe were not practical for modest family households. This is the recipe which the schoolboy sees in his father's newspaper in the 1930 movie One Family. Courtesy of Public Record Office. |

|

| A somewhat whittled down recipe, but with more Empire producing countries credited. Courtesy of Public Record Office |

|

| Courtesy of Public Record Office |

Watch One Family, a 1930 British propaganda film on the King's Christmas Pudding

|

| An Empire Day meeting in Preston in 1909. You will recognise Lord Meath to the left of the mayor |

* Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, chaplain on board His Majesty's ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, anno 1675 to 1679. Charles Knight. London 1825, pp. 127-28.

** Plumcake has pointed out to me that in A Voyage to Virginia, by Colonel Norwood, from A Collection of Voyages and Travels by Awnsham Churchill and John Churchill (1745) Vol. 6 p.153, there is the following diary account of an improvised shipboard Christmas dinner - and the pudding is called a Christmas Pudding,

'Many sorrowful days and nights we spun out in this manner, tille the blessed feast of Christmas came upon us, which we began with a very melancholy solemnity; and yet, to make some distinction of times, the scrapings of the meal-tubs were all amassed together to compose a pudding. Malaga sack, sea water, with fruit and spice, all well fryed in oyl, were the ingredients of this regale, which raised some envy in the spectators; but allowing some privilege to the captain's mess, we met no obstruction, but did peaceably enjoy our Christmas pudding.'

Norwood's voyage took place in 1649, so if Churchill's transcription of Norwood's diary is reliable, then this would mean that this is the earliest reference we have so far found to a Christmas pudding.

Food anthopologist Kaori O' Connor has written a marvellous paper on this subject. I would encourage you to read it. Here is the citation -

Kaori O’Connor, The King's Christmas pudding: globalization, recipes, and the commodities of empire, in

Journal of Global History. Volume 4, Issue 01. March 2009, pp 127 -155.

Ivan was recently interviewed by Michael Mackenzie, the host of the excellent Australian ABC RN First Bite food programme. We chatted about the extraordinary phenomenon of Empire Christmas Pudding, the subject of which Ivan dealt with in a former posting on this blog. Click here to listen to the programme.

Watch a video of Ivan making and discussing the Empire Christmas Pudding.