|

| My favourite Christmas tipple - Punch Royal - but why the orange peel? Recipe and explanation below. |

I was recently given a small job by a television production company to check the historical accuracy of the script of a programme about Christmas drinks. Though it only dealt with a limited number of period tipples, the show, which will be transmitted by the BBC over the holiday period, was fairly well researched and I only identified a few issues that needed changes. One of these was an erroneous statement that 'mulled wine' was first mentioned by the poet Geoffrey Chaucer in 1386. This was probably based on a search on Google which yielded information about the medieval spiced beverage hippocras, a cordial wine used as a digestive after a meal and as a celebratory drink at weddings and other important events. The researcher had come across this line from Chaucer's Merchant's Tale,

'He drynketh Ypocras Clarree and Vernage Of spices hoote tencreessen his corage'.*

Mulled Wine

Making assumptions about how our ancestors ate and drank based on the nature of our contemporary culinary practices is a common error. Food and drink in the past were often very different to our own, as was the culture that surrounded them. Take our modern understanding of mulled wine for instance. Although the word 'mull' starts to occur in the early seventeenth century, recipes for 'mulled ale' and 'mulled wine' do not appear in any frequency until late in the following century. Among the earliest to appear in print are these by the Manchester confectioner Elizabeth Raffald, |

| From Elizabeth Raffald, The Experienced English Housekeeper. Manchester: 1769) |

With its egg yolks and slices of toast, as well as the method of pouring it backwards and forwards from one vessel to another, the mulled wine of Raffald's Georgian Manchester bears little resemblance to that served at the German style Christmas fairs that have been springing up all over England recently. Raffald gives a second recipe for 'mulled wine' which actually contains no wine at all, though I expect this is a mistake, as it is identical to other Georgian recipes for mulled milk, a kind of hot spicy custard served with toast as a supper dish. In 1795 Sarah Martin, cookery writer and housekeeper to Freeman Bower of Killerby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, borrowed Mrs Raffald's book title in her The New Experienced Housekeeper (Doncaster: 1795). However, she did not steal Raffald's mulled wine recipe, as her own version is distinctly different. Its most interesting feature is her very specific use of 'mull' in the context 'mull it backwards and forwards till frothed and smooth', indicating that the verb was being used to describe this to and fro action, rather than meaning 'to heat'.

Our ancestors were very found of comforting winter nightcaps like these, particularly at supper. In a world without central heating or electric blankets, you can understand why these hot beverages were so popular before the dreaded ascent of the stairs to an often ice-cold bed chamber. The medical books of the eighteenth century are full of references to mulled wine, often combined with more powerful medicaments for treating all manner of disorders. Both Raffald's mulled wine and ale, with their fusion of egg yolks, spice and alcohol were really types of caudle, a beverage often consumed in a medical context. When cream or milk was added to the alchemical formula, these restoring beverages were usually called possets. Variations on the theme were legion, often requiring specialist cups or pots in which to to serve the drinks. Mrs Raffald instructs us to serve her mulled wine in a chocolate cup. The two examples illustrated below were made during her lifetime. They are both as far as you can get in terms of elegance from the utilitarian plastic cup out of which I drank some modern mulled wine at the marvellous Arundel Christmas Fair a few weeks go. When it comes to elegance the Georgians knock us into touch every time.

Our ancestors were very found of comforting winter nightcaps like these, particularly at supper. In a world without central heating or electric blankets, you can understand why these hot beverages were so popular before the dreaded ascent of the stairs to an often ice-cold bed chamber. The medical books of the eighteenth century are full of references to mulled wine, often combined with more powerful medicaments for treating all manner of disorders. Both Raffald's mulled wine and ale, with their fusion of egg yolks, spice and alcohol were really types of caudle, a beverage often consumed in a medical context. When cream or milk was added to the alchemical formula, these restoring beverages were usually called possets. Variations on the theme were legion, often requiring specialist cups or pots in which to to serve the drinks. Mrs Raffald instructs us to serve her mulled wine in a chocolate cup. The two examples illustrated below were made during her lifetime. They are both as far as you can get in terms of elegance from the utilitarian plastic cup out of which I drank some modern mulled wine at the marvellous Arundel Christmas Fair a few weeks go. When it comes to elegance the Georgians knock us into touch every time.

|

| Chocolate cup and saucer of soft-paste porcelain painted with enamels with exotic birds amongst bushes, and insects. Chelsea ca.1756. Courtesy V&A. |

Bishop, Lawn Sleeves, Cardinal and Pope

One hot spiced drink, which a few years ago we never heard much about, but which recently has practically gone viral on the web - there are that many postings about it and none of them terribly accurate - is 'Smoking Bishop'. If it sounds vaguely familiar, you may recall it as the Christmas draught that Ebebezer Scrooge promises to Bob Cratchitt towards the end of Charles Dicken's novel A Christmas Carol (London 1842). Scrooge says, 'we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob!'

However, I suspect that Dickens inadvertently coined the name 'smoking bishop'. I am pretty sure that the novelist's intention in using the word 'smoking' was to evoke an image in our mind's eye of a punch bowl emanating clouds of alcoholic steam. This was a great choice of adjective by a skilled wordsmith to create an atmosphere of warmth and good cheer. The drink was commonly known to one and all at the time as just plain 'bishop' and had been since at least the mid-eighteenth century. I have failed to find any instances of the usage 'smoking bishop' before 1841 when A Christmas Carol first appeared in serial form. A few of Dicken's contemporaries started to use the term in their books a few year's later - Charles J. Lever in Arthur O' Leary (London: 1845) and Henry Dier in Dustiana (London: 1850). But by then just about everyone in the English speaking world was familiar with the antics of Ebenezer and Bob and the name Smoking Bishop had been subsumed into the national imagination. No doubt one of you will write to tell me that you have found an instance of the name before 1841 and bang will go my theory! But that would be great. This is the reason why I write this blog. Let us together cut through the bullshit and celebrate the real truth about the history of our food and drink.

The earliest full English recipe for bishop known to me (and it is just plain 'bishop') is to be found in a lovely and incredibly rare book first published in Oxford in 1827 called Oxford Night Caps. This little collection contains recipes for many of the so-called alcoholic nightcaps favoured at the time by the students and dons of the Oxford colleges. In his Year Book (London: 1832), the great Georgian antiquarian William Hone gives a very favourable review of this little forty-two page pamphlet, 'In the evenings of this cold and dreary season, "the dead of winter", a comfortable potation strengthens the heart of the healthy and cheers the spirits of the feeble'. In its pages are to be found numerous recipes for 'potations' such as Rum Fustian, Egg posset, Beer flip and Brown Betty.

|

| Decorative title page of Richard Cook, Oxford Nightcaps (Oxford: 1827) |

The author of Oxford Nightcaps, Richard Cook, opens his book with a discussion of the history of bishop. He suggests that 'it derives its name from the circumstance of ancient dignatories of the Church, when they honoured the University with a visit, being regaled with spiced wine'. He then gives the recipe below,

|

| Probably the first published recipe for bishop from Richard Cook, Oxford Nightcaps. (Oxford: 1827). |

Jonathan Swift wrote the couplet Cook quotes in 1738. It appears to contain the earliest mention of bishop in English. His complete poem consists of just four lines, so I will give the full version here,

Come buy my fine oranges, sauce for your veal,

And charming, when squeezed in a pot of brown ale;

Well roasted, with sugar and wine in a cup,

They'll make a sweet bishop when gentlefolks sup.

J. Swift, 'Women who cry Oranges' from Works. (London:1755) IV. i. 278.

However, in the year that Swift's poem was first published, a recipe for bishop appeared in Sweden in the first edition of a cookery book by Cajsa Warg, Hjelpreda i hushållningen för unga fruentimber. (Stockholm: 1755). In this popular book, which went into many editions, it is called in Swedish 'biskop', though in some later Swedish works the more German 'Bischof' is used. As in Swift's poem the drink is flavoured with roasted oranges rather than the lemon mentioned in Cook's recipe. I am indebted to Madame Berg for this information. Her English translation of the recipe, perhaps the earliest for bishop in Europe, can be found in her comments at the end of this post. It contains some fascinating details. Do any of you know any early German recipes for bischof?

Although I have never seen any evidence that they were ever used in England, in the German and Scandinavian world, bishop was sometimes served from specialist lidded bowls made in the shape of bishops' mitres. A number of these have survived, the earliest dating from the 1750s. Perhaps bishop was adopted from the German speaking world and is not English at all. These extraordinary vessels indicate that the beverage had a high profile on the continent nearly a hundred years before Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol.

Returning to England however, a few other literary men seem to have aquired a taste for bishop well before Dickens wrote of it. Boswell tells us that Dr Johnson was very fond of the beverage and Coleridge in one of his poems calls it 'Spicy bishop drink divine'. The ritual of making Richard Cook's Oxford bishop, especially if you have an open fire, makes for a great kitchen performance. First a lemon has to be spiked with cloves and roasted in front of the fire. This not only releases a flood of essential oil, but also caramelises the surface of the lemon.

|

| Frontispiece from Cajsa Warg, Hjelpreda i hushållningen för unga fruentimber. (Stockholm: 1755). This book contains a recipe for 'biskop' which is much earlier than any published in England. |

|

| A Danish tin glazed earthenware bishops mitre bowl, St. Kongensgade faiance ca.1750. Danish National Museum |

|

| German faience bischofbowle with rococo design and orange handle. ca.1750s. |

|

| German faiance bishop bowl ca.1776. Courtesy of Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin |

|

| Roasting bishop - the clove-spiked lemon toasts in front of the fire |

This done, some cloves, cinnamon, allspice, mace and ginger are added to a half pint of water and the liquid boiled until it reduces to half. The room slowly fills with the delicious fumes of roasting lemon and the simmering spices.

|

| Boiling bishop - cinnamon, mace, ginger, cloves and allspice bubble in simmering water until it reduces to half. |

|

| Flaming bishop - the excess alcohol burns off in a spectacular fireworks display |

|

'Spicy bishop drink divine' - the finished potation 'smokes' in front of the fire with its grate of nutmeg and roasted lemon.

|

Cook's recipe for bishop was quickly plagiarised, appearing word for word two years later in a rather silly book about food and drink called Apician Morsels (London: 1829) by one Dick Humelbergius Secundus. A slightly enlarged edition of Oxford Night Caps was then published in 1830. Fifteen years later Cook's recipe for bishop was also quoted exactly as it was first printed by the celebrated Victorian poet and cookery author Eliza Acton. Curiously she illustrates the recipe with an amusing engraving of some naked cherubs swimming in what resembles a baptismal font!

|

| Cook's recipe quoted word for word in Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery (London: 1845). |

Lawn Sleeves was made with madeira or sherry rather than port. To impart a satiny texture, 'three glasses of hot calves-feet jelly' were added. Cardinal was made the same way as Bishop, but with claret instead of port. Pope was made with champagne using exactly the same method. Another variant called Cider Bishop was made with a bottle of cider, a pint of brandy and two glasses of calves-feet jelly. It seems strange to us today to add hot melted calves-feet jelly, but this also appears in a number of other Oxford nightcaps, such as Negus, Oxford Punch and 'Storative' (Restorative Punch). At this time, this crystal clear nutritious jelly could readily be purchased in a prepared block from the butchers.

Wassail Cup or Swig

Towards the end of his little book Cook discusses the celebrated festive drink Wassail Bowl, which he tells us was known to the fellows of Jesus College as 'Swig'. In 1732 a former student at Jesus, the celebrated Welsh Jacobite Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn (1692 –1749), presented the college with a gargantuan silver punch bowl weighing 200 ounces.

|

| Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, (1692 –1749). Oil on canvas. Michael Dahl. |

Here is Cook's recipe for the swig that was once served annually at the Jesus Christmas feasts from Sir Williams-Wynn's enormous bowl, which holds ten gallons of the stuff,

Cook goes on to tell us that earlier versions of Wassail Cup had roasted apple or crab apples added to the mixture instead of toasted bread. He then gives recipes for both the well-known wassail cup variant Lamb's Wool and the lesser known Brown Betty. Sir Williams-Wynn's great silver bowl is actually a standard Georgian punch bowl. Earlier wassailers had drunk theirs from wooden bowls called mazers. In the cider drinking regions of England these were turned from apple wood and frequently ornamented with seasonal greenery and ribbons.

|

| From Frederick Bishop, The Wife's Own Book of Cookery, (London: nd. ca.1850) |

During the course of the seventeenth century, the wealthy drank their Christmas wassail, usually at Twelfth Day entertainments, from beautifully turned bowls made of lignum vitae and ivory, frequently adorned with silver bands and mounts.

|

| Lignum vitae wassail bowl with silver mounts made for the Grocers' Company. 1693. Courtesy Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. |

|

| Wassail drinking set. Lignum vitae and ivory. 1640-60. Courtesy of the V&A. The curious finial on top of the bowl is a box for storing the spices. |

The form of the wassail bowl was imitated in some of the very earliest punch bowls, some of which had little spice boxes on top as well as the foot and stem typical of the wassail bowls.

|

| Seventeenth century punch bowl in the form of a wassail bowl. Tin glazed earthenware and lignum vitae |

During the course of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, ardent punch made from arrack, rum or brandy started to become as popular as the weaker native wassail drinks made from ale or cider. Usually served hot in the winter months, by the 1780s it was also being chilled with ice, or even frozen into an alcoholic water ice for summer usage.

Punch Royal

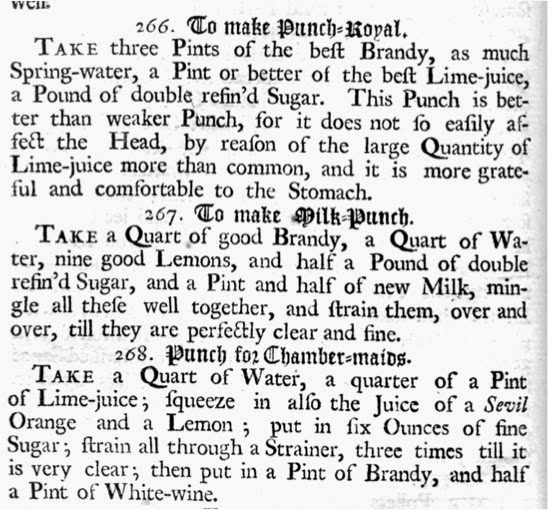

My own favourite Christmas tipple is a drink I first came across in John Nott's The Cook's and Confectioner's Dictionary (London: 1723). Punch Royal is a delicious, but deceptively powerful potation based on brandy and lime juice. It contains no spice and has a lovely clean flavour. I always serve it to guests at my Taste of Christmas Past course in a punch bowl garnished with curling zests of orange peel. Here is Nott's recipe with a couple of others thrown in for good measure.

So why do I serve my punch royal with orange zests hanging over the rim of the punch bowl as illustrated at the beginning of this post? Well over the years I have noticed that many eighteenth and early nineteenth century images of punch drinking show exactly that. Here are a few examples.

|

| Thomas Patch, Detail from A Punch Party (1762) Courtesy National Trust (Dunham Massey) |

|

| Detail from William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation (engraving) 1732. |

|

| Another detail from above. Note the discarded zests of orange peel sharing the floor with the human debris. |

|

| Detail from James Gilray, Anacreonticks in Full Swing. Aquatint 1801. It's that Christmas feeling again! |

|

| Oranges peeled to make long zests for the punch bowl form William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation. Oil Oainting 1732. Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. |

These are just a few of the images in which I have noticed strips of orange zest hanging out of punch bowls, though none are 'several fathoms long'. There is a time span of nearly seventy years between the earliest and latest of these illustrations. I have often wondered what the purpose of this custom was. My pet theory is that these strips of what were probably bitter orange peel, would be hung in the punch to impart a nice citrus flavour. If it became too bitter, the peel was removed (rather like we may pull out a tea bag when the tea gets too strong) and thrown on the floor to join the discarded tobacco pipes, empty wine bottles and human debris who could not take their drink. But this is just a guess. It is still a mystery. So can one of you anacreontick enthusiasts out there enlighten me - but only if you have found some convincing evidence!

Can I draw your attention to the comment by the sharp-eyed Adam Balic, which he has posted below. Adam suggests that these early punch drinkers may have been flaming the zests of peel in the candle flames to flavour the punch in the way that it is sometimes done today in making a number of cocktails.

|

| Whatever nightcap floats your boat this season, Plumcake and I say 'Cheers' and wish you all a Merry Christmas. |

* Merchant's Tale. 365.

While we are on the subject of Christmas, Ivan was recently interviewed by Michael Mackenzie, the host of the excellent Australian ABC RN First Bite food programme. We chatted about the extraordinary phenomenon of Empire Christmas Pudding, the subject of which Ivan dealt with in a former posting on this blog. Click here to listen to the programme.

Listen to Ivan talk about Bishop on BBC Radio 4 Sunday with William Crawley

Listen to Ivan talk about Bishop on BBC Radio 4 Sunday with William Crawley

Ivan in 17th and 18th century dictionaries "zest" has a very specific definition of " Zest (Fr.) the pill of an Orange, or such like, squeezed into a glass of wine, to give it a relish"; "Zest a peel of orange squeezed at the candle so as to give a flavour to the drink" etc. If you look at the painting of "A midnight modern conversation", William Hogarth, c1732, you can see the peel draped punch bowl, a huge pile of discarded peels and also candles. I don't think the latter are there to provide illumination. I think that the peels are being used to flavor the punch after squeezing through a candle. This is still done for some modern cocktails.

ReplyDeleteAnd a very Merry Christmas to you Ivan.

ReplyDeleteHello, thanks your writing these interesting posts!

ReplyDeleteIf you're curious, there is a Swedish recipe for "Biskop" (which simply translates to Bishop) from 1755 but it is quite different from the Oxford 1827 recipe (which sounds more tasty to me, actually!).

Thank you for telling me about the 1755 'biskop'. I would love to see a recipe - in English if it is possible and a citation of the book in which it was published. best regards

DeleteIvan

I tried my best with an English translation, though it's rather difficult for me to translate archaic Swedish! I hopeyou'll get the geist of it.

ReplyDeleteIt's from my facsimile edition of the 1755 cookbook by Cajsa Warg so it is really 100% true to the original.

Here we go:

To make Biskop

Cut into fresh Bitter oranges, and put them onto a gridiron and roast them on an even fire, but turn them so that they may be evenly roasted, but not burnt; then put them into the punch bowl while they're hot with a good amount of sugar, and squeeze all the juice from them with a spoon, and shortly thereafter pour in pontac, and stir well and cover the bowl with a plate, so that the wine may not lose it's fervor. Let stand for 1 or 2 hours, the longer it may rest, the better the flavour from the Bitter oranges may be obtained, which makes this beverage pleasant: he who finds it to his taste to dilute [the Biskop] with water, may to so after his heart. The proportions for this may not be easily described, for Bitter oranges may be small or large; also are they not equally juicy in the zest or the pulp; but if they're large and fully fresh, 4 Bitter oranges may suffice to 3 ordinary bottles of pontac, as long as it [the Biskop] may soak as to obtain the flavour therefrom. With Rhein wine may in the same manner Biskop Roijal be made.

I hope that was readable! I understand Pontak to be a Bourdeaux wine, and Rhein wine is of course white wine of some German variety.

Source: Warg, Cajsa, Hjelpreda i hushållningen för unga fruentimber./(C.W.) Stockholm, tryckt hos Lor. Ludv. Grefing, på desz egen bekostnad 1755., Stockholm, 1755

Thank you so much for this. It is fascinating that a drink called Biskop, so similar to English Bishop was made in Sweden in 1755. The earliest mention of the English version is by the Irish poet and writer Jonathan Swift in the following poem which he composed in 1738.

DeleteCome buy my fine oranges, sauce for your veal,

And charming, when squeezed in a pot of brown ale;

Well roasted, with sugar and wine in a cup,

They'll make a sweet bishop when gentlefolks sup.

J. Swift, 'Women who cry Oranges' from Works. (London:1755) IV. i. 278.

As you can see, Swift's poem was published in London in the very same year that your recipe was printed in Stockholm. Unlike the earliest English recipe for bishop I know, published in 1827, the Swedish version uses bitter oranges just like Swift suggests. Your recipe is much earlier than any that I have found in English cookery texts and has some fascinating details like roasting the oranges on a gridiron and squeezing all the juice from them with a spoon. Incredible! I cannot thank you enough for this wonderful insight into the international dimensions of what I thought was a purely English beverage. The question now is where did this beverage originate? Does anyone out there know of recipes in other European languages?

Cheers! Or should I say Skål!

Ivan

I´m so glad the recipe was of interest to you!

DeleteI did some additional armchair research and it appears that the mention of the beverage appears no earlier than in the 1750s in Sweden. Interestingly, the spelling variant "Bischoff" seems to have been equally or more popular as the century progressed, which *may* suggest that the drink is of German origin. Then again, in a Swedish cookbook from 1879, the author simply states that it's an English beverage.

Finally, an 1835 recipe for "Bischoff" that I found was rather similar to the Cajsa Warg one from 1755 but called for lemon zest, cinnamon and cloves as well, which pushes is a little closer (flavour-wise) to the Oxford recipe. It also suggested that the recipe could be improved by not roasting the oranges but simply use the zest and juice instead!

Fascinating, these little things!

Again, thank you for your interesting and informative posts; I will look for your work in the Pemberley series when I get the time to watch it!

Un BLOG instructivo y bello!!!

ReplyDeleteVoy a necesitar mucho tiempo para ponerme al día, pero en ello estaré.

SALUDOS AMISTOSOS:))))

Conxita

Grab 50% OFF on personalised luggage tags with your own photos online. Talk to our Production Manager Luggage Tags Printing. The reason of their high demand lies in the fact that they are light in weight as well as stylish in nature.

ReplyDelete